Mathematically Unlikely

A blog following the process of becoming a mathematics and science teacher by reconciling the scientific with the emotional.

April 10, 2011

The math in pop culture

I have edited together a video. For math.

As I'm spending my precious few weekend hours trying to figure out video editing, I can't help but wonder how much difference it might make for my students. While I might hope that they will start seeing math in their world and in pop culture, I know that's an unreasonable hope. However, if I can make a couple of them think that math class is not such an awful place to be, I think I will be on the right track.

March 7, 2011

February 17, 2011

December 8, 2010

Video Review

This was the video we reviewed. Check it out!

And here's my review.

November 17, 2010

Just try harder

From high school, I distinctly remember making the statemen "I don't have to try very hard because I'm pretty good at math." I said it with confidence and with certainty; I did well on math tests without studying, I must be good at math.

As I progressed in my post secondary degree, I started to realize that I actually had to try, not just in math, but in all my subjects. I started to make statements like "I studied every day for the entire term, of course I did well in advanced organic chemistry."

I remember being frustrated by a friend who continually told me that I didn't have to worry about tests, assignments and the like because I was smart and always did well. She brushed it off as being beside the point whenever I pointed out that I spent hours in profs offices, that I studied regularly, and that I had done every single not-for-marks assignment. She was never willing to recognize how much effort I put into my courses. She continued to believe that I was simply "smart."

I've been learning about students' belief systems regarding intelligence and how those beliefs affect their academic performance. It's astounding. From what I've read, there are two general beliefs held: the belief that intelligence is an inherent, fixed quality and the belief that intelligence is a fluid quality that can be improved by applying oneself. The fascinating thing is how these beliefs affect student outcomes:

|

| Intelligence is fixed | Intelligence is malleable |

| Students’ goal | To look smart, even if they learn less | To learn, even if they make mistakes |

| What does failure mean? | Failure means low intelligence | Failure means low effort, poor strategy |

| What does effort mean? | Effort means low intelligence | Effort activates and uses intelligence |

| Strategy after difficulty | Less effort | More effort |

| Self-defeating defensiveness | High | Low |

| Performance after difficulty | Impaired | Equal or improved |

If students believe that effort is a way to be intelligent, they tend to persist in both enjoyment of subjects and are better able to sustain effort in a difficult problem. If students believe that you’re born with a certain amount of intelligence, every failure (or perceived failure) strikes at the heart of something valued-their intelligence.

Can we change these beliefs? And if so, how?

November 3, 2010

Set the hook

I wholeheartedly agree.

There is also an idea that in order for students to want to learn there should be a "hook," an idea to reel them in and make them interested enough in the subject to want to continue learning.

Once again, I think this makes sense.

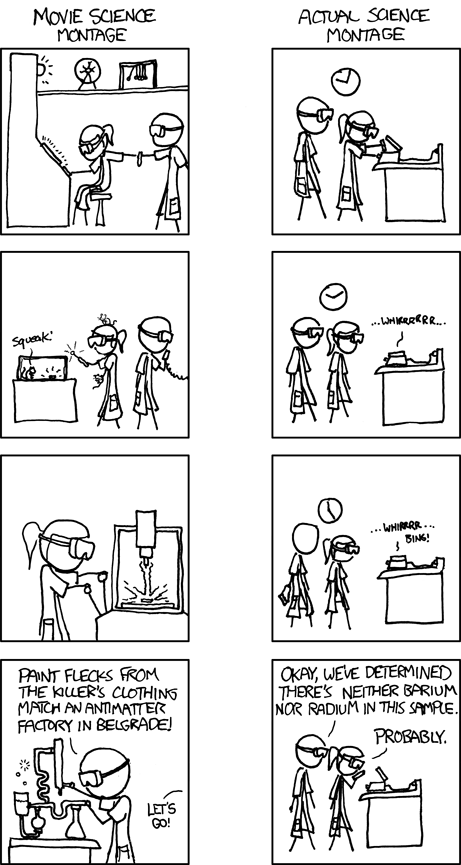

In science we have thousands of "teachable moments" when we can do fascinating demonstrations, or discuss the science of the last CSI episode. Chemistry in particular is full of bangs and changing colours.

Students get dismayed that there is so much to learn that is not the bangs, colour changes, or "fun stuff." Most science is fascinating, intriguing, active, and leads to fascinating results. But it is not instantaneous and it does demand a certain level of automaticity within specific, relatively boring skill sets. Knowing how to do molar calculations is neither exciting nor motivating, but it is necessary for true scientific literacy in chemistry.

So how do we bridge the gap? How do we engage in those "teachable moments" while still providing adequate practice that will make our students competent practitioners?