A blog following the process of becoming a mathematics and science teacher by reconciling the scientific with the emotional.

December 8, 2010

Video Review

This was the video we reviewed. Check it out!

And here's my review.

November 17, 2010

Just try harder

From high school, I distinctly remember making the statemen "I don't have to try very hard because I'm pretty good at math." I said it with confidence and with certainty; I did well on math tests without studying, I must be good at math.

As I progressed in my post secondary degree, I started to realize that I actually had to try, not just in math, but in all my subjects. I started to make statements like "I studied every day for the entire term, of course I did well in advanced organic chemistry."

I remember being frustrated by a friend who continually told me that I didn't have to worry about tests, assignments and the like because I was smart and always did well. She brushed it off as being beside the point whenever I pointed out that I spent hours in profs offices, that I studied regularly, and that I had done every single not-for-marks assignment. She was never willing to recognize how much effort I put into my courses. She continued to believe that I was simply "smart."

I've been learning about students' belief systems regarding intelligence and how those beliefs affect their academic performance. It's astounding. From what I've read, there are two general beliefs held: the belief that intelligence is an inherent, fixed quality and the belief that intelligence is a fluid quality that can be improved by applying oneself. The fascinating thing is how these beliefs affect student outcomes:

|

| Intelligence is fixed | Intelligence is malleable |

| Students’ goal | To look smart, even if they learn less | To learn, even if they make mistakes |

| What does failure mean? | Failure means low intelligence | Failure means low effort, poor strategy |

| What does effort mean? | Effort means low intelligence | Effort activates and uses intelligence |

| Strategy after difficulty | Less effort | More effort |

| Self-defeating defensiveness | High | Low |

| Performance after difficulty | Impaired | Equal or improved |

If students believe that effort is a way to be intelligent, they tend to persist in both enjoyment of subjects and are better able to sustain effort in a difficult problem. If students believe that you’re born with a certain amount of intelligence, every failure (or perceived failure) strikes at the heart of something valued-their intelligence.

Can we change these beliefs? And if so, how?

November 3, 2010

Set the hook

I wholeheartedly agree.

There is also an idea that in order for students to want to learn there should be a "hook," an idea to reel them in and make them interested enough in the subject to want to continue learning.

Once again, I think this makes sense.

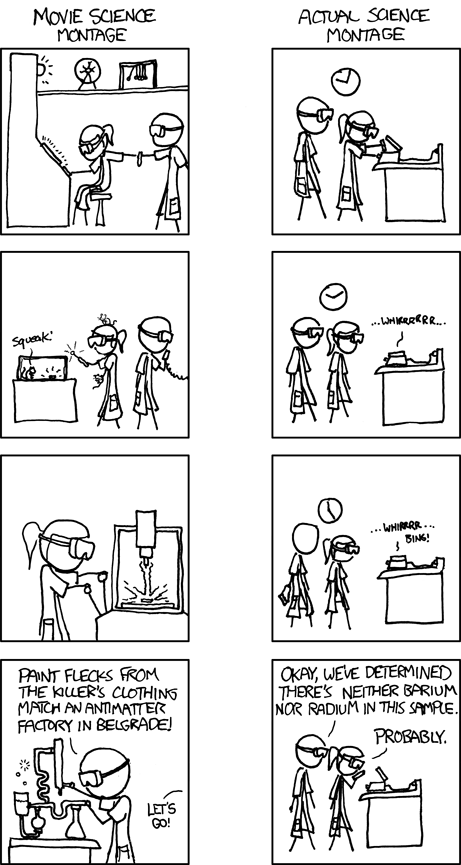

In science we have thousands of "teachable moments" when we can do fascinating demonstrations, or discuss the science of the last CSI episode. Chemistry in particular is full of bangs and changing colours.

Students get dismayed that there is so much to learn that is not the bangs, colour changes, or "fun stuff." Most science is fascinating, intriguing, active, and leads to fascinating results. But it is not instantaneous and it does demand a certain level of automaticity within specific, relatively boring skill sets. Knowing how to do molar calculations is neither exciting nor motivating, but it is necessary for true scientific literacy in chemistry.

So how do we bridge the gap? How do we engage in those "teachable moments" while still providing adequate practice that will make our students competent practitioners?

October 27, 2010

A fabulous math rant!

October 1, 2010

The mathematics of surfing

I edited this image in Piknic. I changed the contrast and sharpness, the temperature, added text and cropped the image.

I edited this image in Piknic. I changed the contrast and sharpness, the temperature, added text and cropped the image. This photo I edited in Sumopaint. I added text, layer effects, and changed the contrast. This editor was much less intuitive for me. However, I think this would be a useful tool if I was using a photograph as an image, rather than as a photograph. Being able to insert shapes might help illustrate the geometric nature of the world.

This photo I edited in Sumopaint. I added text, layer effects, and changed the contrast. This editor was much less intuitive for me. However, I think this would be a useful tool if I was using a photograph as an image, rather than as a photograph. Being able to insert shapes might help illustrate the geometric nature of the world.September 23, 2010

The math literacy problem

From the get-go, I was a math person. Math makes sense to me. Its patterns and rules, its hidden intricacies, and its ability to describe the incredibly complicated process of, say, falling. But it seems that insight is not universal. Or is it?

Is it that people don't understand "math" or that they got stuck somewhere along the way and never felt success again? Is it so unusual to understand patterns? Or to follow that if I have pies each cut into 6 and I have 5 slices that I have somewhat less than one pie? Is it a challenge to see that when an object is thrown up into the air, its distance above the ground is predictable via an equation? Are those ideas the hard part, or is it that people got stuck somewhere and never moved on?

It's culturally acceptable to be bad at math. Why? Why is it okay to be illiterate in math, but not okay to be illiterate in reading?

I'm not suggesting that math makes sense to everyone. You actually don't have a math brain? Fine. But before you decide that, are you sure that it's not that somewhere along the way you stumbled over an idea?

My greatest challenge as a math teacher, I predict, will be finding those stumbles and getting students past them while moving through the curriculum. If I can do that for even half my students, will the generation coming through be less inclined to say "I'm not a math person"?

Math problems are a puzzle. There's a beginning and an end, but how you get between those two points is entirely up to you. You know if you solved the puzzle if you got the right answer. There's a great deal of satisfaction in solving the puzzle.

For explanations of math at any level

http://www.math.com/

To learn more about Mathletics, the online program engaging students in fun and challenging math learning

http://www.mathletics.ca/

For super fun, content specific math games (seriously addictive)

http://www.mathplayground.com/